Sin #3 - Fostering a Culture of Debt

Over the last two decades, departing Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan has affected many people in many ways. Few people understand the impact he has had on their lives - how he has helped transform a culture.

After eighteen years as the world's most powerful central banker, he has changed the way people think about money, credit, and most importantly, he has changed the way people view debt.

After eighteen years as the world's most powerful central banker, he has changed the way people think about money, credit, and most importantly, he has changed the way people view debt.Debt, a pariah to generations following the Great Depression, has been embraced by recent generations.

Recent generations, that is, who are now far enough removed from the tragedy of the 1930s that history's lessons of excess credit and debt have been forgotten. Debt, always a tempting seductress, has been raised to new levels of respectability under the tutelage of Mr. Greenspan.

Many, emboldened by rising asset prices, have completely lost what had been for centuries a largely uninterrupted natural aversion to borrowing money.

Benjamin Franklin and Adam Smith abhorred debt.

Changing Attitudes

Today, borrowing against equity in real estate occurs at rates never seen before. Mortgage equity withdrawal was unheard of generations ago - a second mortgage was the last recourse for a family in trouble.

Today it is routine.

Septuagenarians shake their heads as they see young people living lifestyles which don't square with what they know of their incomes and expenses. Debt it seems has not taught any hard lessons lately - debt has become too friendly, too tame, and too forgiving.

Nowhere is the cultural change more apparent than on television - a constant din of pitchmen offering new and innovative ways of extending credit to ordinary people.

"I'm up to my eyeballs in debt" one ad begins, as if that condition is somehow funny.

In a truly disturbing symbol of how times have changed, the once mighty General Motors now hawks home equity loans and EZ cash-out refinancing through its Ditech.com subsidiary - the only GM group that has been consistently profitable in recent years.

A once dynamic and innovative economy has become increasingly dependent on borrowing money to fund consumer spending. This spending, in turn, produces economic growth and most accept this condition as just another reality - another fact of life.

With a zero savings rate, Americans borrow and spend paying little heed to the mounting debt or the implications for the future. As long as asset prices rise faster than debt, household balance sheets don't seem to matter, and bills never really come due.

Someday, maybe soon, the accumulating debt will matter.

Household Balance Sheets

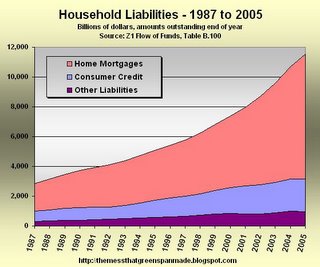

The magnitude of the new debt over the last two decades is evident when looking at household liabilities over this period. Household debt gently rose during the 1990s until the bursting of the stock market bubble necessitated massive monetary stimulus from the Fed.

The stimulus came in the form of multi-generational lows in interest rates which, when combined with a largely unregulated mortgage lending industry, ignited a housing boom the likes of which the world has never seen.

That's a lot of mortgage debt - over eight trillion dollars in all. In the last three years alone, nearly three trillion dollars of new mortgage credit has been extended - first mortgages, second mortgages, home equity loans, and lines of credit.

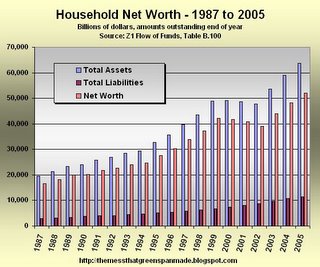

Some dismiss concerns of too much debt by pointing to the bottom line.

Debt, they say, is not a problem because household balance sheets are the best they've ever been. Today, household net worth does look impressive - against a meager 12 trillion dollars in debt stands a hefty 64 trillion dollars in assets.

A closer look at net worth, however, shows that while liabilities have marched steadily upward, assets can go up or down. Not down by much, at least not in this chart, but down nonetheless.

A closer look at how different types of assets have behaved during the first half of the decade shows a neat handoff between equities and real estate. Stocks had run their course, interest rates were slashed to forty-year lows, and housing markets across the land began to boom.

One rapidly rising asset class having exhausted itself, another asset class began to rise rapidly, easing the pain that, historically, would have been expected.

A crisis had been averted. In fact, many would say that the cure worked better than could possibly have been expected, given the circumstances.

In the last few years, with soaring property values, household net worth has now hit all time highs despite the trillions of dollars in new mortgage debt. More debt, it seems had not only saved the day, but ushered in a new era of prosperity and rising living standards.

Ordinary people are now wealthier than ever before, and the effects of more credit and debt have confirmed what many had come to conclude over the years - debt is good.

The cultural transformation is now complete.

A Good Time

But as Alan Greenspan prepares to exit the stage, leaving behind mountains of debt, where does that leave us? With all this new debt and prosperity comes a potential problem.

What happens if real estate assets suffer the same fate as equities did a few years ago? Or, what if real estate values simply go flat for an extended period of time?

Since debt lingers long after assets lose their glow, how might the bottom line look then? How might the culture change as a result? Warren Buffet famously said some time ago, "Give me a trillion dollars and I'll show you a good time too!".

Was this Alan Greenspan's motive all along?

With almost nine trillion dollars of new household debt created during his years at the Federal Reserve, and having changed the way the entire Anglo-Saxon world views debt, is this all that Alan Greenspan ever really wanted?

To show everyone a good time?