Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

‘Hard landing' forecast for U.S.

Hold on to your hats. It may be time to turn your U.S. portfolio on its head.

That's because there's growing evidence that the U.S. economic cycle is more advanced than is generally recognized — and that there is a higher risk that the economy could be in for a hard landing, not a soft one.

This is the view of David Rosenberg, North American economist for investment dealer Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc. in New York.

“Practically every indicator at our disposal tells us that we are very late cycle, and the historical record also suggests that the next wave after the Fed has inverted the entire yield curve is either a hard landing or a very bumpy soft landing,” Mr. Rosenberg said in a commentary, referring to the U.S. Federal Reserve Board's interest rate policies. “Either way, the economy is going to have some sort of a ‘landing,' which is far different than a ‘takeoff.'”

Noting that the U.S. economy enjoyed a good “takeoff” in 2003-04, he added that he “would highly recommend that investors switch their portfolios to a complete inverse of what worked and didn't work at that earlier stage of the cycle.”

Economic models run by Merrill Lynch suggest the odds of the economy enduring a hard landing range from 40 to 80 per cent, well above the consensus view, which pegs them at just 27 per cent, Mr. Rosenberg said.

In a decision Aug. 8, the U.S. Fed left its benchmark federal funds rate unchanged at 5.25 per cent, following 17 consecutive hikes dating back to June, 2004. The rationale was that slowing economic growth will curb inflation.

A key element of the slowdown on which the Fed is banking, as it seeks to guide the U.S. economy to a soft landing, is an orderly turndown in the U.S. real estate market, where a housing boom has been a major driver of growth.

However, Mr. Rosenberg argued that a two-year low in housing starts reported last week, along with the first downturn in 15 years in the number of building permits issued and a record six-month decline in the National Association of Home Builders housing market index, means the slowdown is much more precipitous than the U.S. central bank wanted to see. “The real estate turndown is proving to be a tad less ‘orderly' than policy makers were hoping for,” he said.

In fact, Mr. Rosenberg cited a speech delivered last Wednesday by Dallas Federal Reserve Board president Richard Fisher, who, quoting what someone he called a friend and a major home builder had told him, said: “This is the roughest, most sudden correction we have seen in the housing market.”

The Merrill Lynch economist argues that the housing “recession” will last at least four more quarters and, through direct and indirect impacts, carve almost two percentage points of U.S. economic growth. “That may not be enough to generate an overall recession ... but seeing as such a pace of activity would take the unemployment rate back to over 5½ per cent, it sure would feel like a recession for a whole lot of folks,” he said.

The universe does not look quite so bleak to Tobias Levkovich, chief U.S. equity strategist at Citigroup Inc. in New York.

He noted Monday that although stocks in the utilities and telecommunications sectors tend to underperform following a plunge in the housing market index, those in the financial and consumer staples sectors tend to outperform.

“While it may be somewhat obvious that people still need to buy food and sundries and would defer more extravagant expenditures in the midst of a housing slowdown, it is encouraging that the stocks indeed trade the same way,” Mr. Levkovich said. “In contrast, consumer discretionary stocks can be hammered when things sour in the housing market.”

That's because there's growing evidence that the U.S. economic cycle is more advanced than is generally recognized — and that there is a higher risk that the economy could be in for a hard landing, not a soft one.

This is the view of David Rosenberg, North American economist for investment dealer Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc. in New York.

“Practically every indicator at our disposal tells us that we are very late cycle, and the historical record also suggests that the next wave after the Fed has inverted the entire yield curve is either a hard landing or a very bumpy soft landing,” Mr. Rosenberg said in a commentary, referring to the U.S. Federal Reserve Board's interest rate policies. “Either way, the economy is going to have some sort of a ‘landing,' which is far different than a ‘takeoff.'”

Noting that the U.S. economy enjoyed a good “takeoff” in 2003-04, he added that he “would highly recommend that investors switch their portfolios to a complete inverse of what worked and didn't work at that earlier stage of the cycle.”

Economic models run by Merrill Lynch suggest the odds of the economy enduring a hard landing range from 40 to 80 per cent, well above the consensus view, which pegs them at just 27 per cent, Mr. Rosenberg said.

In a decision Aug. 8, the U.S. Fed left its benchmark federal funds rate unchanged at 5.25 per cent, following 17 consecutive hikes dating back to June, 2004. The rationale was that slowing economic growth will curb inflation.

A key element of the slowdown on which the Fed is banking, as it seeks to guide the U.S. economy to a soft landing, is an orderly turndown in the U.S. real estate market, where a housing boom has been a major driver of growth.

However, Mr. Rosenberg argued that a two-year low in housing starts reported last week, along with the first downturn in 15 years in the number of building permits issued and a record six-month decline in the National Association of Home Builders housing market index, means the slowdown is much more precipitous than the U.S. central bank wanted to see. “The real estate turndown is proving to be a tad less ‘orderly' than policy makers were hoping for,” he said.

In fact, Mr. Rosenberg cited a speech delivered last Wednesday by Dallas Federal Reserve Board president Richard Fisher, who, quoting what someone he called a friend and a major home builder had told him, said: “This is the roughest, most sudden correction we have seen in the housing market.”

The Merrill Lynch economist argues that the housing “recession” will last at least four more quarters and, through direct and indirect impacts, carve almost two percentage points of U.S. economic growth. “That may not be enough to generate an overall recession ... but seeing as such a pace of activity would take the unemployment rate back to over 5½ per cent, it sure would feel like a recession for a whole lot of folks,” he said.

The universe does not look quite so bleak to Tobias Levkovich, chief U.S. equity strategist at Citigroup Inc. in New York.

He noted Monday that although stocks in the utilities and telecommunications sectors tend to underperform following a plunge in the housing market index, those in the financial and consumer staples sectors tend to outperform.

“While it may be somewhat obvious that people still need to buy food and sundries and would defer more extravagant expenditures in the midst of a housing slowdown, it is encouraging that the stocks indeed trade the same way,” Mr. Levkovich said. “In contrast, consumer discretionary stocks can be hammered when things sour in the housing market.”

Friday, August 18, 2006

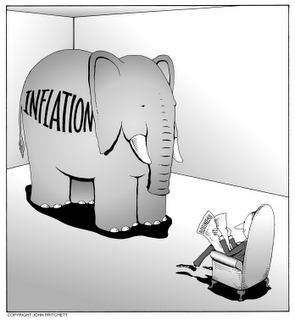

Repeat After Me! There is no Inflation!

Things may cost a little more, but there is no inflation. Dual income families are struggling to keep up, but there is no inflation. In Canada, Statscan tells us that inflation is contained and in the U.S. the Bureau of Labor Statistics says that inflation is under control. The numbers don't lie!

We haven't seen a negative savings rate since the Great Depression and the current level of personal debt is unprecendented, but there is no inflation.

Statistics regarding inflation can always be manipulated but if you ask the "man on the street" if general prices are:

1) about the same as they were a few years ago

2) a little bit higher

3) a lot higher,

you'd get a true gauge of inflation.

For now, inflation remains the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Canadian Inflation Numbers Flawed?

Flawed CPI numbers from Statscan? Say it isn't so. As you know, inflation numbers are manipulated in so many ways that they are practically meaningless anyway. This type of admission is no big deal except for Canadians that rely on indexed pensions and other inflation-linked investments, to maintain a reasonable standard of living.

StatsCan admits past CPI data flawed

August 16, 2006 | Steven Lamb

Statistics Canada has revealed that it has been miscalculating the consumer price index for the past five years, understating inflation on average by 0.1% since early 2001. The understatement stems from a problem in the formula used to calculate price increases for hotel accommodation. Since 2001, StatsCan has calculated this element of the overall CPI to have fallen by 16%, when it actually rose 32%.

At least one economist says the effects will be limited.

"Although one doesn't want outright mistakes, the bigger picture is that inflation is only measured approximately — it may in fact overstate the cost of living for a number of reasons," says Avery Shenfeld, senior economist at CIBC World Markets. "No economic measure is reported with precision, but one does want to avoid creating errors beyond those inherent in measuring inflation."

He says investors holding real return instruments and workers whose earnings are indexed to inflation should not hold their breath waiting for any remedy, though.

"There will be some who will be disappointed that they were 'cheated' out of a small payment that they should have received," he says. "The CPI is not going to be revised. It's water under the bridge at this point."

People currently receiving pension benefits may fare a little better, but only if StatsCan factors the miscalculation into its next CPI report and adjusts the official rate of inflation to reflect the error.

"If they try to incorporate or reflect the miscalculation in the next CPI figures, there might be an impact, but we can't judge what that would be until we know if and by how they are going to readjust the number," says Karen DeBortoli, director of the Canadian research and innovation centre at Watson Wyatt Worldwide. "There is currently no information about that that I have seen."

Even then, any adjustment would be minimal, according to Steve Bonnar, principal of Towers Perrin.

"Those pension plans that provide automatic increases based on inflation will just do a one time catch-up next time around to reflect the error," he says. "Those sponsors that provide ad hoc increases periodically round so generously that a difference of 0.1% is just not going to be very meaningful."

Earlier this year, StatsCan admitted it had miscalculated national productivity. That error was traced back to an anomaly in the number of working days in 2005. Still, Shenfeld says StatsCan's reputation is pretty solid.

"To its credit, Statistics Canada on all of these occasions has admitted its error as opposed to masking a change in a revision," says Shenfeld. "One never knows if other statistical agencies are as forthcoming or if they present corrected data as 'revised' and not necessarily conceding that an error was made. Virtually everyone, at some point makes a mistake.

"Their reputation is quite solid and I don't think this will seriously sully their reputation."

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Savings Accounts, Mutual Funds, Stocks, Bonds? Who Needs Them? We Own a House!

More use homes as main asset

Instead of building a nest egg for retirement, a growing number of homeowners are putting themselves in a debt trap.

Economists and investment advisers say that more Americans are relying on their homes as their primary asset for retirement. These retirees-to-be reckon they can always tap the expanding wealth in their residence to cover their leisure years.

The reasoning goes something like this: Need some cash? No problem, just get a home-equity line of credit. And because home values have skyrocketed in recent years in places such as the East Bay, homeowners figure they can replace the equity lost from taking out the loan within a year or two. Plus, down the road, they assume they can always just sell the house or get another loan to raise some quick cash for retirement.

"People are making the mistake of thinking they live inside a big piggy bank," said Libby Mihalka, president of Altamont Capital. "They don't realize it can all snowball out of control very quickly. Their house is not an ATM."

"This is a form of financial insanity," said Frank Fernandez, chief economist with the Securities Industry Association. "You are digging yourselves deeper into debt using an asset that could decline in value."

"Among my East Bay clients, I often see a person's retirement plan and equity in their home comprise well over 90 percent of their net worth," Valentine said. "Among Peninsula clients, it's only about 50 percent."

It's 1987 All Over Again!

Looking for similarities to the stock market crash of 1987? Look no further.

Bio: Nouriel Roubini, is a Professor of Economics at the Stern School of Business at New York University. His applied academic research includes seminal work in international macroeconomics, global macro policies, financial crises in emerging markets and their resolution, and the reform of the international financial architecture. As a leading economist in the field of international macroeconomics, Nouriel has had significant senior level policy experience. Numerous policy appointments include former assignments as Senior Economist for International Economics at the White House Council of Economic Advisors, Senior Advisor to the Under Secretary for International Affairs at the U.S. Treasury, Director of the Office of Policy Development and Review at the U.S. Treasury. He has been a policy and research consultant at the IMF since 1985, and is a member of many leading policy forums and organizations including the Bretton Woods Committee, the International Roundtable of the Council of Foreign Relations, the NBER and the CEPR. Nouriel is a consultant for a wide range of policy institutions, Central Banks, and a number of senior executives from major financial institutions.

Nouriel Roubini | Aug 12, 2006

In my recent “recession call” blog I made the observation that current economic and financial conditions in the U.S. eerily resemble those that led to the stock market crash in October 1987. Let me elaborate on the quite worrisome and scary similarities between 2006 and 1987.

In 1987, like in 2006, a new Fed Chairman had been chosen; then Alan Greenspan this year Ben Bernanke.

In 1987, the new Fed Chairman was initially viewed with skepticism by markets and investors; the same for Bernanke today. The lionization of Greenspan as the “Maestro” or his "God-on-Earth" reputation was a much later phenomenon that emerged only in the 1990s; in 1987 investors were extremely skeptical of his skills and ability to be a strong leader of the Fed in difficult times. Ditto for Bernanke today who still needs to establish his credibility and gain the full respect of markets and investors.

In 1987, Greenspan started his term in a period when inflation was rising and there were concerns about inflationary pressure becoming excessive. That is why in 1987 he started his term by raising the Fed Funds rate by 100bps. Ditto for Bernanke who inherited high and rising inflation and raised rates three times, by 75bps, since he became Fed Chairman earlier this year.

In 1987, the relatively inexperienced Greenspan did not know how to properly communicate his message and he rattled markets. He presented his views in the wrong forum by giving an interview to a Sunday television news show where he expressed his concerns about inflation; the next day stock markets sharply wobbled. He learned his lesson, realized the risks to his reputation, made a mea culpa, never gave again a TV interview for the following 20 years and became altogether Delphic in his public pronunciations. Ditto for Bernanke: after a congressional testimony on April 27th that was read by investors as dovish, he made the famous flap with CNBC anchor Maria Bartimoro telling her that he had been misunderstood and was more hawkish than market perceived him. The next day – when Bartimoro reported this – equity markets sharply contracted and Bernanke’s reputation was shaken. Bernanke then made his own public mea culpa and you can be sure that - like Greenspan - he will never speak again to any TV reporter, either in private or in public.

In 1987, the biggest external problem of the U.S. was the large current account deficit that had been the result of the twin deficits of the Reagan years. Unsustainable tax cuts and excessive military spending (remember the pie-in-the-sky Star Wars project) in the Reagan I administration led to a strong dollar and a large current account deficit; after 1985 the dollar started to fall driven by the unsustainable external imbalance. In 2006, we bear the consequences of the reckless fiscal policies – unsustainable tax cuts and runaway military spending in reckless foreign adventures like Iraq (pie-in-the-sky dreams of imposing "democracy" in the Middle East) – that led to large twin deficits since 2001. And since 2002 the dollar has started to fall under the pressure of the external imbalance.

In 1987, in spite of the fall of the dollar since the Plaza agreement of 1985, the current account deficit was still large because of the delayed – J-curve – effects of the depreciation and because the still large fiscal deficits and low private savings kept national savings low. Then, the U.S. started to blame its trading partners, Germany and Japan, and their "weak" currencies for being at fault for the continued US trade deficit. The political scare mongering in the US was that a rising export giant like Japan would leading to the hollowing out of the US manufacturing sector; trade frictions with Japan – on cars, semiconductors, etc. – became heated and accusations of “unfair” trade were rampant. Then, the US started to put pressure on Germany and Japan to let their currencies – the mark and the yen – to appreciate significantly more relative to the US dollar. Today, the scare mongering on “unfair” trade has China as its scapegoat and victim. The US, instead of blaming its own policies that led to low private and public savings for its external deficit, is blaming China and its currency policies for these external imbalances. As in 1987 there is the terror that China will hollow out the US traded sector with its unstoppable export boom. And trade tensions are boiling.

The tensions on trade came to a boil in October 1987 when the markets were already nervous about the economy, inflation, higher interest rates, an inexperienced and initially clumsy Fed Chairman and a soaring trade deficit. The announcement of a large U.S. trade deficit on October 14 was the tipping point. Following this news, Treasury Secretary James Baker strongly suggested the need for a fall in the dollar and made implicit threat that the reluctance of Germany and Japan to let the mark and yen to appreciate could be met with retaliatory trade actions. The following day – the infamous Black Monday of October 19th 1987, the stock market crashed: the Dow Jones Industrial Average went into a free fall, down 508 points, losing 22.6% of its total value. The S&P 500 collapsed by 20.4%, dropping from 282.7 to 225.06. This was the largest loss that Wall Street had ever experienced in a single day. Technical factors, such as the growth of derivative instruments trading and inappropriate risk management tools (delta hedging that could hedge little in a fat-tail event of systemic turmoil and instead exacerbated the herding reaction of the market) added to the disorderly financial meltdown.

Today, the tensions with China on the trade deficit and the RMB revaluation are reaching a similar tipping point. China is dragging its feet on the currency issue while its trade surplus with the US is rising; Hank Paulson was chosen as Treasury Secretary principally to nudge China into moving; Schumer is bringing his 27.5% China tariff bill to a vote by the end of September and the Treasury has to present another “China Manipulation” report in the fall; the economy is slowing and mid-term elections are increasing the protectionist mood of Congress both for what concerns trade in goods and asset protectionism (see the CNOOC-Unocal case, the Dubai Ports case; and the pressure to reform the CFIUS process in ways that will be highly restrictive towards inward FDI); markets are hedgy and nervous and investors more risk averse after the May-June financial markets turmoil; the growth of derivative instruments is much more massive than 20 years ago; and wishful and self-serving arguments that such derivative instruments allow to hedge and distribute risk rather than concentrate it more are even more senseless today than they were two decades ago. So, the risks of a systemic crisis are serious and grave.

In these conditions it usually takes little to rattle markets and trigger a meltdown. Hopefully Paulson will be smarter and more discrete than Baker in avoiding bullying China and the countries that are financing the US current account deficit; it is both bad manner to bite the hand that feeds you (or, as Italians say, to spit into the plate from which you are happily eating) and also reckless financial behavior as the US badly needs this cheap foreign financing. Markets are already hedgy on their own and international investors are increasingly risk averse. The US needs to borrow every year almost another trillion US dollars – on top of all the previous stock of past borrowing - to finance its still increasing external deficit. Thus, the risks that things will get out of hand and trigger a financial meltdown of the scale that was experienced in 1987 are serious.

Today you have trade protectionism and asset protectionism; hedgy and trigger-happy investors and rising geopolitical risks; the risk of a disorderly fall in the US dollar; a slush of financial derivatives that are a black box that no one truly understands (the operational risk in credit derivatives is only the tip of much larger systemic risk iceberg in these instruments, as the pricing of these instruments has not been tested in a real cycle of increasing corporate bankruptcies); increasing VARs and growing levels of leverage; frothy markets where years of too easy money have created bubbles galore - the latest in housing - that are ready to burst; a bubble of thousands of new hedge funds with inexperienced managers that have no supervision or regulation of their activities; risk management techniques in financial institutions that miserably fail to truly stress test for fat tail events; hedging strategies that – like in 1987 – can hedge nothing once everyone is rushing to the doors and dumping assets at the same time; and a housing markets whose rout may trigger systemic effects through the mortgage backed securities market and the non-transparent hedging activities of the GSEs.

This is a toxic and combustive mix of volatile elements that can lead to a financial explosion and meltdown. And it may take any small match to trigger it: a trade war scare mongering, scorning the foreigners that finance you with restrictions to inward FDI, talking down the dollar to bully China and the US trade partners, a flip-flopping monetary policy, a further spike in oil prices, an event of terrorism or a wider Mid East conflict, a housing market rout rattling the MBS market, the collapse of a large and systemically- relevant hedge fund or of another highly-leveraged financial institution, a Chapter 11 event for a major US corporation such as Ford or GM leading to systemic effects in the credit derivatives market. There is indeed an embarrassment of riches in terms of factors that can trigger a financial meltdown. A single factor among those discussed above may be enough to trigger it; and the risk that a variety of such factors may simultaneously emerge is increasing.

So, to paraphrase Bette Davis in "All About Eve": Fasten your seat belts; it’s gonna be a bumpy ride ahead for financial markets and the global economy…

Monday, August 14, 2006

Dissent at the Fed?

Missing a wingbeat

JEFFREY LACKER has held a vote on the rate-setting committee of America's Federal Reserve for less than a year. But on August 8th he did something no committee member has done since June 2003: he voted against the chairman, Ben Bernanke. Mr Lacker, head of the Richmond Fed, thought his fellow central bankers should raise interest rates for the 18th time in a row. Instead, they decided to pause in their long migration back to a temperate monetary policy, holding the federal funds rate at 5.25%.

This split decision was accompanied by a statement that might most charitably be described as “deliberative”. The Fed admitted core inflation was high (2.4% in the year to June, according to its preferred measure); it probably won't remain so, but if it does the Fed will start tightening again, falling in behind the man from Richmond.

Downsize Me!

Americans are carrying a lot of excess weight and desperately want to slim down. No, not their waistlines -- in the size of their homes.

"Steeply deteriorating." "Hard landing." "Kaput." These are some of the terms used by analysts to describe the slowing of the U.S. housing market. And with the glory days of home-price appreciation now over, some homeowners are declaring, "Downsize Me!"

A huge gap between the supply of homes for sale and demand for housing means prices are leveling off -- and could tumble.

David Horwitz and his wife, Diane, are the type of homeowners looking to streamline their expenses and unload their roomy homes for more humbler abodes.

The Horwitzes, both semi-retired, just moved into a 1,200 square-foot apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan after living in a 2,200 square-foot home in Scarsdale, New York.

"Our property taxes went down by 1,000 percent, the ConEd (bill) was cut by two-thirds and the cost of home maintenance was reduced by at least 50 percent," said David Horwitz. "No gardener, no roofer cleaning gutters, no tree spraying, no snow removal, no exterior painting every six or seven years."

The Horwitzes, who have no mortgage, plan to reside in the apartment for a while, so even if prices fall it is of little significance to them.

"Homeowners are probably sensing now may be the right time to get the best price before the market cools further," Ramirez said. "Some of these homebuyers are empty-nesters now finding their homes are larger than what they need and more than they can handle."

The average home size went from 1,500 square feet in 1970 to more than 2,400 square feet in 2005. During the same period, the average household size declined, from 3.11 to 2.59, he said.

"Steeply deteriorating." "Hard landing." "Kaput." These are some of the terms used by analysts to describe the slowing of the U.S. housing market. And with the glory days of home-price appreciation now over, some homeowners are declaring, "Downsize Me!"

A huge gap between the supply of homes for sale and demand for housing means prices are leveling off -- and could tumble.

David Horwitz and his wife, Diane, are the type of homeowners looking to streamline their expenses and unload their roomy homes for more humbler abodes.

The Horwitzes, both semi-retired, just moved into a 1,200 square-foot apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan after living in a 2,200 square-foot home in Scarsdale, New York.

"Our property taxes went down by 1,000 percent, the ConEd (bill) was cut by two-thirds and the cost of home maintenance was reduced by at least 50 percent," said David Horwitz. "No gardener, no roofer cleaning gutters, no tree spraying, no snow removal, no exterior painting every six or seven years."

The Horwitzes, who have no mortgage, plan to reside in the apartment for a while, so even if prices fall it is of little significance to them.

"Homeowners are probably sensing now may be the right time to get the best price before the market cools further," Ramirez said. "Some of these homebuyers are empty-nesters now finding their homes are larger than what they need and more than they can handle."

The average home size went from 1,500 square feet in 1970 to more than 2,400 square feet in 2005. During the same period, the average household size declined, from 3.11 to 2.59, he said.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Charity Lending Scams!

IRS: Charity lending is scam -- Down-payment plans called misleading

Calling them scams, the Internal Revenue Service plans to revoke the charitable status of down-payment assistance programs that have fueled the business of Dominion Homes and other builders.

"So-called charities that manipulate the system do more than mislead honest homebuyers and ultimately jack up the cost of the home," IRS Commissioner Mark W. Everson said in a statement. "They also damage the image of honest, legitimate charities."

Federal law prohibits home builders from helping customers directly with down payments. For years, however, builders have partnered with charities to funnel money to buyers. The IRS is examining 185 such charities, which have helped hundreds of thousands of people buy homes with government-backed mortgages.

Typically, a charity gives the customer a down payment, and the builder reimburses the charity plus a processing fee. The programs offer a similarly popular service for individual home sellers, usually through their real-estate agents.

The programs help buyers with the 3 percent down payment required for a government-insured Federal Housing Administration mortgage. Many of those buyers get in over their heads financially and later lose their houses, studies show.

Nearly a third of FHA loans nationally last year involved charitable down-payment assistance to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Without their charitable status, down-payment assistance programs can't do business with the FHA.

A Dispatch series, "Brokered Dreams," in September detailed the risks to home buyers and taxpayers of such down-payment assistance. The stories focused on the partnership between Dublin-based Dominion and the Nehemiah Corp. of America, a California charity that pioneered the business strategy.

Nehemiah, the largest program, received $143 million in down-payment money from sellers in 2004, according to the most recent IRS filings. Seller "donations" accounted for more than 99 percent of Nehemiah's revenue.

David Dillen, president of Colony Mortgage, partnered with Dominion on hundreds of loans involving down-payment assistance. But Dillen said HUD was long overdue in shutting down the gift programs.

"What the hell took them so long?" he said. Colony followed HUD's rules but didn't agree with them. "It was a big scam."

Calling them scams, the Internal Revenue Service plans to revoke the charitable status of down-payment assistance programs that have fueled the business of Dominion Homes and other builders.

"So-called charities that manipulate the system do more than mislead honest homebuyers and ultimately jack up the cost of the home," IRS Commissioner Mark W. Everson said in a statement. "They also damage the image of honest, legitimate charities."

Federal law prohibits home builders from helping customers directly with down payments. For years, however, builders have partnered with charities to funnel money to buyers. The IRS is examining 185 such charities, which have helped hundreds of thousands of people buy homes with government-backed mortgages.

Typically, a charity gives the customer a down payment, and the builder reimburses the charity plus a processing fee. The programs offer a similarly popular service for individual home sellers, usually through their real-estate agents.

The programs help buyers with the 3 percent down payment required for a government-insured Federal Housing Administration mortgage. Many of those buyers get in over their heads financially and later lose their houses, studies show.

Nearly a third of FHA loans nationally last year involved charitable down-payment assistance to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Without their charitable status, down-payment assistance programs can't do business with the FHA.

A Dispatch series, "Brokered Dreams," in September detailed the risks to home buyers and taxpayers of such down-payment assistance. The stories focused on the partnership between Dublin-based Dominion and the Nehemiah Corp. of America, a California charity that pioneered the business strategy.

Nehemiah, the largest program, received $143 million in down-payment money from sellers in 2004, according to the most recent IRS filings. Seller "donations" accounted for more than 99 percent of Nehemiah's revenue.

David Dillen, president of Colony Mortgage, partnered with Dominion on hundreds of loans involving down-payment assistance. But Dillen said HUD was long overdue in shutting down the gift programs.

"What the hell took them so long?" he said. Colony followed HUD's rules but didn't agree with them. "It was a big scam."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)