Despite the constant denials of the economists at the National Association of Realtors, the reality is beginning to hit and hit hard in the U.S. Housing Market. Inflated markets around the nation are starting to face the reality that the seemingly unstoppable housing market has stalled and the repercussions on the overall economy, remain to be seen.

This is an article from the LA Times, discussing the recent problems in Merced California:

The Land of the Open House

Merced, once the state's hottest housing market, is headed back to being, well, Merced again.

By David Streitfeld, Times Staff Writer

March 25, 2006

MERCED, Calif. — Where did everyone go? Real estate agent Mark R. Gregory is holding an open house to sell a nearly new three-bedroom on a corner lot, and it's as if the Earth had been emptied.

Last year, this Central Valley city enjoyed the state's hottest real estate market. Sure, things have slowed since then, but Gregory possesses a salesman's indestructible optimism.

He put a sign on the lawn, a note on the Internet, an ad in the paper. He's hoping for investors from the coast marveling at how much house you can buy here for $359,000. Or local couples looking to move up into something nicer. Or Bay Area workers willing to make the long commute.

Three hours quietly pass. At 4 p.m., the agent pulls up the sign and locks the door. Total visitors: zero.

"It's like everyone got together and said, 'Let's not buy for a while,' " Gregory says.

After five increasingly wild years, the great real estate boom appears to be coming to a close. The Commerce Department reported Friday that sales of new homes nationwide plunged 10.5% in February, about five times the drop analysts predicted.

In places such as Los Angeles, which have diverse economies, the consequences could be mild. In other communities, where prices became untethered from reality long ago and real estate not only drove the economy but virtually became the economy, the fallout could be much more turbulent.

Merced — a farming town once known, if known at all, as a place campers turned off California 99 on their way to Yosemite National Park — is falling into the latter category.

The good times have already ended here, in the same way slamming into a wall reduces your speed. A house will fetch 20% less today than it did last summer, brokers say, assuming it finds a buyer at all.

Just a little while ago, Merced was an investor's dream. The Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight reported this month that prices in the city and surrounding area increased 31% in 2005. The housing agency ranked Merced first in price appreciation in California and ninth in the nation.

That already feels like ancient history, an era when agents would list a property and within hours people would be madly bidding against one another. In five years, Gregory never had a listing that lasted longer than four days.

The number of agents registered to sell in Merced went from 200 to 1,200 as property prospered. Mortgage brokers, title companies and other processing firms flocked to town. One new complex, the Plaza at El Portal, accommodates Chicago Title, Wells Fargo Mortgage, New Freedom Mortgage, First American Title, Building Showcase Interiors, Moonlight Development and Sunlight Development. There's almost nothing that isn't connected to housing.

The phenomenon occurred throughout the Central Valley. According to the Housing Enterprise Oversight numbers, the leading edge of the nation's real estate mania was not San Francisco or Manhattan or Miami, no matter how giddy those markets seemed to their residents, but in some little-known agricultural communities.

The housing agency's No. 1 U.S. city for price appreciation over the last five years was Madera, an old logging town northwest of Fresno that rose 144%. Yuba City, north of Sacramento, was second. Third place went to a Florida city, Port St. Lucie. Fresno and Merced, both at 142%, rounded out the top five. (Los Angeles prices increased 131%, still above the state average of 117%.)

Andrew Leventis, a Housing Enterprise Oversight economist, contemplated this ascending arc in a region that is not a tourist destination or retirement haven, where incomes are not growing and unemployment is perpetually high. He then used an un-economist word: "Shocking."

"It's difficult to know what was driving these high rates of appreciation," Leventis said.

To people in Merced, however, there's little mystery. This was a classic bubble, where people paid increasingly higher prices because they were sure that someone would come along and pay even more. Economists call this the "greater fool" theory.

In 2003 and 2004, carloads of investors would come down from the Bay Area and up from Los Angeles. They would see a $200,000 house and say, "Wow, if this were on the Westside or in Berkeley, it would be worth $750,000, easy. Let's offer $225,000 to make sure we get it."

Then the seller across the street would say, "If that place was worth $225,000, I'm going to ask $250,000."

It helps that Merced is a pleasant place, with an appealing main street and lovely spring evenings. The first new UC campus in 40 years is being built in stages on the outskirts. Twenty-five thousand students will eventually study there, greatly benefiting the local economy.

Sunday, March 26, 2006

Thursday, March 23, 2006

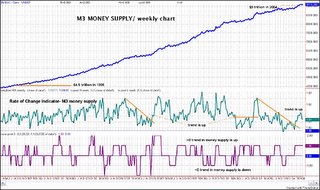

Goodbye M3

I remember when I was studying for my Bachelor of Commerce Degree at the University of Toronto, in our economics class we discussed M1, M2, and M3 reporting. At the time, I didn't appreciate the importance of these measures and certainly had no idea how big these numbers would eventually become. After all, it was the 80's and the economic landscape was quite different than it is now. We were still talking about the failure of Reagonomics and their impact on the economy. We were still quoting Gordon Gecko's "Greed Is Good" speech from Wall Street.

Well today, it's official! No more M3.

Here's a great article from Tim McMahon from BullnotBull:

Goodbye M3- What is the Government hiding?

by Tim McMahon, Editor

I'm surprised we haven't heard much in the news about this but as of March 23rd 2006 the government will no longer be publishing the M3 money supply data. Most people probably say "Who Cares?" Right?

But you should care! And here's why:

"The Federal Reserve tracks and publishes the money supply measured three different ways-- M1, M2, and M3.

These three money supply measures track slightly different views of the money supply.

The most restrictive, M1, only measures the most liquid forms of money; it is limited to currency actually in the hands of the public. This includes travelers checks, demand deposits (checking accounts), and other deposits against which checks can be written.

M2 includes all of M1, plus savings accounts, time deposits of under $100,000, and balances in retail money market mutual funds.

But that is all small potatoes, M3 includes all of M2 (which includes M1) plus large-denomination ($100,000 or more) time deposits, balances in institutional money funds, repurchase liabilities issued by depository institutions, and Eurodollars held by U.S. residents at foreign branches of U.S. banks and at all banks in the United Kingdom and Canada."

In other words, M3 tracks what the big boys are doing with the money. This includes US dollars held in banks in Canada and the UK (called Eurodollars) not to be confused with the Euro which is the standard currency of Europe.

So the question immediately arises why would the FED stop tracking this? The reason they give is that:

1) it will save money

2) That all the money that it tracks is tracked by other indicators.

First of all, since when is the government interested in saving money? I've never heard of a government program being cut once it is on the books. There are stories of government offices being created for the purpose of WWII and continuing on for decades even though the employees had absolutely nothing to do!

If they were eliminating M1 they could say the money is included in other indicators because M1 is included in M2 and M3. If they eliminated M2 it would be included in M3 but what is M3 included in?

So, perhaps I'm just suspicious by nature but it begs the question, what are they trying to hide?

Well, if you've read any of our other articles you will know that inflation and the money supply are very tightly integrated. Increases in the money supply are the direct cause of inflation. (See Inflation- Cause and effect and Inflation Definition).

With all its efforts at "Tracking Inflation" most everyone agrees that the last thing the Government really wants is for the general public to know how much it is stealing out of your pockets through inflation.

Inflation has been called "the hidden tax" and that is exactly what it is. When the Government "prints" extra money what do you think it does with it? It spends it of course!

What would happen if you started writing checks (creating money) from an account that was empty? You'd end up in jail! But that is exactly what the government is doing when it creates money out of thin air.

Enron isn't the only one who knows how to cook the books!

For years now in an effort to hide the actual amount of inflation, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (who tracks the inflation rate) has been erasing inflation through a trick called "hedonics".

Basically they say since a new computer is faster than an old one you get more for your money, so they adjust the price down.

So even though a new computer might cost you $500 they say since it is twice as fast, it is really only costing you $250. But try to explain that to "Best Buy" when you want to pick one up and see how far you get.

They use the same logic for cars and other things. Everyone who studies it knows the Government is fudging the numbers, but it has gotten so bad that now they have to hide the M3 altogether.

Again I ask why? Well, I have a theory. The U.S. trade deficit is running at an annual rate of about $800 billion. That means we are spending $800 billion more than we are earning in the world markets. Basically, we are sending dollars overseas (primarily to China) and they are sending us stuff.

Well, what are the Chinese doing with all that money we are sending them? Are they buying our stuff? Nope! That would reduce our trade deficit. They are actually saving about 50% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In other words, as a Nation, they save half of what they make or about 1.1 Trillion Dollars a year.

On a nationwide basis (this includes Government, Business and personal) the U.S. only saves 13% of its GDP. But on a personal level the picture is much worse. Chinese households save 30% of what they earn while U.S. households save less than Zero! On average, we actually spend .4% more than we earn every year.

It is hard to imagine but it is true. So what are the Chinese doing with all that extra money? They can't just pile it up in their garage (if they had one). So what are they doing with it? Buying back our debt. The Chinese are huge buyers of U.S. Government Treasury securities.

Someone said recently that it's hard to tell who's crazier. "One spends money it hasn't got and the other sells to people who can't pay."

Basically, the Chinese are loaning us the money to buy their stuff. And the Government is printing the money to do it. So my theory is that in order to hide all the money that is being created and sent to China the government is going to stop tracking M3.

The Smoking Gun

It is no coincidence that the M3 went up an annualized 9.4% in the last three months and an annualized 17.2% in December alone and now the FED wants to stop tracking it!

Why bother tackling a problem of this magnitude when you can just bury the evidence? Who wants to leave a "smoking gun" laying around? A 9.4% increase in money supply should translate into a 9.4% inflation rate (if GDP produces exactly enough to counteract obsolescence).

Even if there is a 1% increase in the supply of goods, that still means that we really have 8.4% inflation rather than the 3.6% the BLS is telling us.

In order for the 3.6% number to be true-- we would have to have 5.8% more stuff than last year (9.4% - 3.6% = 5.8%). Do you have 5.8% more stuff than last year? I didn't think so.

The writing is on the wall. When the Government starts hiding data the problem is big! If this trend continues, inflation is going to come roaring back big time. We will see the late 70's all over again. The war is Iraq and the Billions in Hurricane damage have to be paid for somehow and the "hidden tax" is the easy way out.

Now is the time to begin stocking up on inflation hedges.

Tim McMahon, Editor

InflationData.com

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Economic Suicide

James Turk from safehaven.com has written an excellent article on the sad state of affairs in the U.S. Economy. This is a must-read sobering article that encapsulates the glaring problems that the U.S. Government, the Fed, and the rest of the world continue to ignore. Is there a happy ending/soft landing in the cards? Unlikely. Not even Neo in The Matrix could dodge this many bullets!

March 16, 2006

Economic Suicide

by James Turk

Anybody who has been lending money to the US federal government by buying T-Bills and its other debt instruments received a brutal one-two punch last week. It was hopefully a sobering experience, causing them to question why they would want to hold any US government paper.

The Washington Post landed the first punch with the following report on March 6th. "WASHINGTON -- Treasury Secretary John Snow notified Congress on Monday that the administration has now taken "all prudent and legal actions," including tapping certain government retirement funds, to keep from hitting the $8.2 trillion national debt limit…Treasury officials, briefing congressional aides last week, said that the government will run out of maneuvering room to keep from exceeding the current limit sometime during the week of March 20."

The second punch was delivered a couple of days later by this Dow Jones Newswires dispatch: "WASHINGTON (Dow Jones) -- The U.S. government ran a monthly budget deficit of $119.20 billion in February, an all-time monthly record that was still slightly less than forecast, according to a Treasury report Friday. The February federal government deficit was 5% greater than a year earlier, according to the Treasury Department's monthly budget statement."

These two reports make clear the dire financial straits the federal government is facing, but its financial position is even worse than it appears. The $8.2 trillion debt limit -- that has proven inadequate to meet the federal government's borrowing needs -- covers only its direct liabilities. In other words, this $8.2 trillion is the total amount of dollars owed to all the holders of US government debt instruments. Excluded from this total debt are all of the federal government's other liabilities, which total another $38 trillion. In "The 2005 Financial Report of the United States Government", US Comptroller General David Walker reported that "the federal government's fiscal exposures now total more than $46 trillion, up from $20 trillion in 2000."

Yes, it's insane. But it's even more insane that people buy the US government's T-Bonds and T-Bills thinking that they are a safe, low-risk investment. Maybe they used to be that, but things change. US government debt instruments are no longer a safe place to park your dollars. To substantiate this assertion, here are some shocking facts to mull over.

1) REVENUE -- Federal revenue peaked at $2.03 trillion in 2000, and then declined for three years, bottoming in 2003 at $1.78 trillion. That's never happened before. Revenue typically declines during a recession, but the most it has ever declined before was two years in a row, during the severe recession of 1958 and 1959. Revenue has rebounded the last two years and reached $2.15 trillion in 2005, but in constant 2000-dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation), revenue remains 6.3% below that received in 2000.

2) EXPENDITURES -- While the federal government's revenue has been constrained, not so with expenditures, which have continued to soar. They were $2.47 trillion in 2005, an alarming 38.2% above the federal government's expenditures in 2000. Expenditures soared even in constant 2000-dollars, scoring a shocking 21.8% increase over the five years from 2000 to 2005.

3) RELIANCE UPON DEBT -- As a consequence of constrained revenue and uncontrolled spending, the federal government has come to increasingly rely upon debt in order to obtain the dollars it spends with gay abandon. In 2000, 1.1% of the federal government's cash flow (revenue plus the annual increase in debt) came from new debt. This reliance on debt grew to 20.4% in 2005. In other words, for every $100 spent by the federal government in 2005, $20.40 came from borrowed money, compared to only $1.10 in 2000.

4) INTEREST RATES -- Of all the major expenditure categories of the federal government, only one declined from 2000 to 2005 -- interest expense. It paid $361.9 billion in interest in 2000, and its interest expense burden fell to $352.3 billion in 2005. During this period, the federal debt climbed 40.5% from $5.63 trillion to $7.91 trillion. So given this increase in debt, it is obvious that the federal government's interest expense burden declined for only one reason -- interest rates fell. In fact, the average interest rate paid by the federal government on its debt in 2000 was 6.4%; it was only 4.6% in both 2004 and 2005.

5) INTEREST EXPENSE BURDEN -- During the 1990's, 24.0% of the federal government's revenue on average was used to pay interest on its debt. During the Bush administration that burden has declined to only 17.5% on average. The reason is that the 5.2% average interest rate paid by the federal government during the Bush administration so far is significantly less than the 7.2% rate it paid on average in the 1990's. It is clear that the lower interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve after the 2000 stock market peak have favorably impacted the federal government's budget. Lower interest rates reduced its interest expense burden, thereby making the deficits incurred so far during the Bush administration much smaller than they would have been if higher interest rates prevailed.

The above facts are indeed shocking as they clearly highlight that both the runaway growth in federal spending during the Bush administration and the resulting deterioration in the financial position of the federal government have been cloaked and little noticed because interest rates have been falling in recent years. So the above facts therefore make the immediate future frightening because as we all know, the Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates.

What will happen to the federal government's financial condition now that the Federal Reserve is raising rates in order to try suppressing the growing inflationary pressures in the economy? The federal government faces a potentially toxic mix of constrained revenue, soaring expenditures, ballooning debt and rising interest rates.

The federal government desperately needs strong economic activity in order to generate the highest possible tax revenue to decrease its reliance on debt. But rising interest rates work against this objective. Rising interest rates dampen economic activity. We have already seen what has happened to the housing market since the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates.

In addition to adversely impacting revenue, rising interest rates also have an unfavorable impact on expenditures. This impact is purely mathematical. A 6% average interest rate on $8.2 trillion of debt results in a higher interest expense burden than a 4.6% rate.

Thus, higher interest rates restrain tax revenue while increasing the level of expenditures. Together these factors worsen the budget deficit, which then causes the federal government to borrow even more money. The resulting higher level of debt leads to a greater interest expense burden, further worsening the deficit. Consequently, the federal government is rapidly moving to the point where its borrowing becomes an increasingly important source of the dollars that it needs to meet its interest expense obligations.

It is clear that these circumstances create a vicious circle where the federal government borrows money to obtain the dollars needed to meet its debt obligations. This condition is not sustainable, and it will end in one of two alternatives -- either the dollar is saved or it isn't. If the vicious circle is not addressed and corrected, it will turn into a death spiral in which the dollar is destroyed.

To explain this point, the federal government will never default on its debt. With the ever-helping hand of the Federal Reserve and the banking system, the federal government will always come up with the dollars it needs to meet its interest expense and other debt obligations. But if the vicious circle described above is not addressed, the federal government will repay its debt obligations with dollars that are worth less and less until they become worthless when the death spiral occurs.

The vicious circle does two things. First, it increases the supply of dollars by creating 'out of thin air' the dollars needed by the federal government to meet its debt obligations. The second point is less obvious but just as pernicious. The vicious circle lessens the demand for the dollar as people over time come to understand the ruinous, underlying dynamics of what's happening to the currency. Higher supply and lower demand mean only one thing -- the purchasing power of the dollar is being inflated away.

These circumstances are not new. They are experienced by every fiat currency sooner or later when the discipline of the gold standard is removed. The discipline of the gold standard is needed to constrain government spending. In the absence of that discipline, a fiat currency inevitably reaches the vicious circle. In fact, it's even happened before with the dollar.

The dollar was in a vicious circle during the waning years of the Carter administration. Paul Volcker was appointed Federal Reserve chairman to break the vicious circle, and he did it by raising interest rates. He kept raising interest rates until real rates (nominal interest rates less the inflation rate) soared to greater than 6%, historically a phenomenally high rate. It was not surprising therefore that the demand for the dollar started rising, thereby breaking the vicious circle and saving the dollar from a death spiral. But Mr. Volcker had an advantage not available today to Mr. Bernanke.

Back then the federal debt was not the burden it is today. Recall that the US was the largest creditor nation in the world back then. The total level of dollar debt was not only much less, but manageable in the environment of rapidly rising interest rates and the high real interest rates ushered in by Mr. Volcker.

Today the US is the world's largest debtor. The US savings rate is negative. American home owners have consumed most of the equity in their houses. In short, the federal government and many consumers are borrowing just to try keeping their head above water. What's worse, there is all the uncertainty arising from trillions of dollars of outstanding financial derivatives, essentially none of which existed during Mr. Volcker's era.

In short, Mr. Bernanke cannot raise interest rates the way Volcker did, which I believe is well understood by both Mr. Bernanke and Mr. Greenspan. After all, look at what happened during the last year of so of Mr. Greenspan's tenure at the Fed. He raised interest rates, but throughout this period, real interest rates remained close to zero and at times were negative, which is a condition that creates a highly inflationary framework for the dollar. In other words, there was a lot of jawboning from Mr. Greenspan to save the dollar from inflation by raising interest rates, but he did not even come close to following in the footsteps of Mr. Volcker. Mr. Bernanke won't either.

Today's monetary system is not only broken, it's completely crazy. For this reason I found the following quote in the current issue of Barron's to be of interest. It's by Richard Daughty, from the March 8th issue of his newsletter, The Mogambo Guru ( 9241 54th St. N., Pinellas Park, Fla. 33782): "What a scam! The week [before last], the Fed snaps its fingers and creates $2.2 billion, and then uses it to buy $2.2 billion in government debt! What in the hell can you do but laugh at the sheer audacity! Somehow, a government creating more and more money and spending it is not, for the first time in history, going to turn out to be a bad thing? And especially one where the money is just paper and computer blips that they can create on a whim? Of course, I sigh wearily as I note that the banks themselves are in on the scam, and they bought up another $13 billion in government debt [the week before last]. Foreign central banks continue to soak up government debt, and they swallowed another $7.6 billion [that] week, too. The government sells debt to get money to spend on its deficits, and the bank creates the money to buy the debt. Debt and money supply both expand, and it expands to create a bigger and more expensive government! And higher prices. This is economic suicide!"

Indeed, it truly is "economic suicide", but it's even worse than that. It's also monetary homicide. The dollar as we know it is being killed, poisoned by debt from the hand of the federal government with its accomplices in the Federal Reserve and the banking system. So far it's been a slow death, with few people watching, but that's about to change. With the horrific new amounts of debt being injected into the dollar's weary remains, its death is not far off.

March 16, 2006

Economic Suicide

by James Turk

Anybody who has been lending money to the US federal government by buying T-Bills and its other debt instruments received a brutal one-two punch last week. It was hopefully a sobering experience, causing them to question why they would want to hold any US government paper.

The Washington Post landed the first punch with the following report on March 6th. "WASHINGTON -- Treasury Secretary John Snow notified Congress on Monday that the administration has now taken "all prudent and legal actions," including tapping certain government retirement funds, to keep from hitting the $8.2 trillion national debt limit…Treasury officials, briefing congressional aides last week, said that the government will run out of maneuvering room to keep from exceeding the current limit sometime during the week of March 20."

The second punch was delivered a couple of days later by this Dow Jones Newswires dispatch: "WASHINGTON (Dow Jones) -- The U.S. government ran a monthly budget deficit of $119.20 billion in February, an all-time monthly record that was still slightly less than forecast, according to a Treasury report Friday. The February federal government deficit was 5% greater than a year earlier, according to the Treasury Department's monthly budget statement."

These two reports make clear the dire financial straits the federal government is facing, but its financial position is even worse than it appears. The $8.2 trillion debt limit -- that has proven inadequate to meet the federal government's borrowing needs -- covers only its direct liabilities. In other words, this $8.2 trillion is the total amount of dollars owed to all the holders of US government debt instruments. Excluded from this total debt are all of the federal government's other liabilities, which total another $38 trillion. In "The 2005 Financial Report of the United States Government", US Comptroller General David Walker reported that "the federal government's fiscal exposures now total more than $46 trillion, up from $20 trillion in 2000."

Yes, it's insane. But it's even more insane that people buy the US government's T-Bonds and T-Bills thinking that they are a safe, low-risk investment. Maybe they used to be that, but things change. US government debt instruments are no longer a safe place to park your dollars. To substantiate this assertion, here are some shocking facts to mull over.

1) REVENUE -- Federal revenue peaked at $2.03 trillion in 2000, and then declined for three years, bottoming in 2003 at $1.78 trillion. That's never happened before. Revenue typically declines during a recession, but the most it has ever declined before was two years in a row, during the severe recession of 1958 and 1959. Revenue has rebounded the last two years and reached $2.15 trillion in 2005, but in constant 2000-dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation), revenue remains 6.3% below that received in 2000.

2) EXPENDITURES -- While the federal government's revenue has been constrained, not so with expenditures, which have continued to soar. They were $2.47 trillion in 2005, an alarming 38.2% above the federal government's expenditures in 2000. Expenditures soared even in constant 2000-dollars, scoring a shocking 21.8% increase over the five years from 2000 to 2005.

3) RELIANCE UPON DEBT -- As a consequence of constrained revenue and uncontrolled spending, the federal government has come to increasingly rely upon debt in order to obtain the dollars it spends with gay abandon. In 2000, 1.1% of the federal government's cash flow (revenue plus the annual increase in debt) came from new debt. This reliance on debt grew to 20.4% in 2005. In other words, for every $100 spent by the federal government in 2005, $20.40 came from borrowed money, compared to only $1.10 in 2000.

4) INTEREST RATES -- Of all the major expenditure categories of the federal government, only one declined from 2000 to 2005 -- interest expense. It paid $361.9 billion in interest in 2000, and its interest expense burden fell to $352.3 billion in 2005. During this period, the federal debt climbed 40.5% from $5.63 trillion to $7.91 trillion. So given this increase in debt, it is obvious that the federal government's interest expense burden declined for only one reason -- interest rates fell. In fact, the average interest rate paid by the federal government on its debt in 2000 was 6.4%; it was only 4.6% in both 2004 and 2005.

5) INTEREST EXPENSE BURDEN -- During the 1990's, 24.0% of the federal government's revenue on average was used to pay interest on its debt. During the Bush administration that burden has declined to only 17.5% on average. The reason is that the 5.2% average interest rate paid by the federal government during the Bush administration so far is significantly less than the 7.2% rate it paid on average in the 1990's. It is clear that the lower interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve after the 2000 stock market peak have favorably impacted the federal government's budget. Lower interest rates reduced its interest expense burden, thereby making the deficits incurred so far during the Bush administration much smaller than they would have been if higher interest rates prevailed.

The above facts are indeed shocking as they clearly highlight that both the runaway growth in federal spending during the Bush administration and the resulting deterioration in the financial position of the federal government have been cloaked and little noticed because interest rates have been falling in recent years. So the above facts therefore make the immediate future frightening because as we all know, the Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates.

What will happen to the federal government's financial condition now that the Federal Reserve is raising rates in order to try suppressing the growing inflationary pressures in the economy? The federal government faces a potentially toxic mix of constrained revenue, soaring expenditures, ballooning debt and rising interest rates.

The federal government desperately needs strong economic activity in order to generate the highest possible tax revenue to decrease its reliance on debt. But rising interest rates work against this objective. Rising interest rates dampen economic activity. We have already seen what has happened to the housing market since the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates.

In addition to adversely impacting revenue, rising interest rates also have an unfavorable impact on expenditures. This impact is purely mathematical. A 6% average interest rate on $8.2 trillion of debt results in a higher interest expense burden than a 4.6% rate.

Thus, higher interest rates restrain tax revenue while increasing the level of expenditures. Together these factors worsen the budget deficit, which then causes the federal government to borrow even more money. The resulting higher level of debt leads to a greater interest expense burden, further worsening the deficit. Consequently, the federal government is rapidly moving to the point where its borrowing becomes an increasingly important source of the dollars that it needs to meet its interest expense obligations.

It is clear that these circumstances create a vicious circle where the federal government borrows money to obtain the dollars needed to meet its debt obligations. This condition is not sustainable, and it will end in one of two alternatives -- either the dollar is saved or it isn't. If the vicious circle is not addressed and corrected, it will turn into a death spiral in which the dollar is destroyed.

To explain this point, the federal government will never default on its debt. With the ever-helping hand of the Federal Reserve and the banking system, the federal government will always come up with the dollars it needs to meet its interest expense and other debt obligations. But if the vicious circle described above is not addressed, the federal government will repay its debt obligations with dollars that are worth less and less until they become worthless when the death spiral occurs.

The vicious circle does two things. First, it increases the supply of dollars by creating 'out of thin air' the dollars needed by the federal government to meet its debt obligations. The second point is less obvious but just as pernicious. The vicious circle lessens the demand for the dollar as people over time come to understand the ruinous, underlying dynamics of what's happening to the currency. Higher supply and lower demand mean only one thing -- the purchasing power of the dollar is being inflated away.

These circumstances are not new. They are experienced by every fiat currency sooner or later when the discipline of the gold standard is removed. The discipline of the gold standard is needed to constrain government spending. In the absence of that discipline, a fiat currency inevitably reaches the vicious circle. In fact, it's even happened before with the dollar.

The dollar was in a vicious circle during the waning years of the Carter administration. Paul Volcker was appointed Federal Reserve chairman to break the vicious circle, and he did it by raising interest rates. He kept raising interest rates until real rates (nominal interest rates less the inflation rate) soared to greater than 6%, historically a phenomenally high rate. It was not surprising therefore that the demand for the dollar started rising, thereby breaking the vicious circle and saving the dollar from a death spiral. But Mr. Volcker had an advantage not available today to Mr. Bernanke.

Back then the federal debt was not the burden it is today. Recall that the US was the largest creditor nation in the world back then. The total level of dollar debt was not only much less, but manageable in the environment of rapidly rising interest rates and the high real interest rates ushered in by Mr. Volcker.

Today the US is the world's largest debtor. The US savings rate is negative. American home owners have consumed most of the equity in their houses. In short, the federal government and many consumers are borrowing just to try keeping their head above water. What's worse, there is all the uncertainty arising from trillions of dollars of outstanding financial derivatives, essentially none of which existed during Mr. Volcker's era.

In short, Mr. Bernanke cannot raise interest rates the way Volcker did, which I believe is well understood by both Mr. Bernanke and Mr. Greenspan. After all, look at what happened during the last year of so of Mr. Greenspan's tenure at the Fed. He raised interest rates, but throughout this period, real interest rates remained close to zero and at times were negative, which is a condition that creates a highly inflationary framework for the dollar. In other words, there was a lot of jawboning from Mr. Greenspan to save the dollar from inflation by raising interest rates, but he did not even come close to following in the footsteps of Mr. Volcker. Mr. Bernanke won't either.

Today's monetary system is not only broken, it's completely crazy. For this reason I found the following quote in the current issue of Barron's to be of interest. It's by Richard Daughty, from the March 8th issue of his newsletter, The Mogambo Guru ( 9241 54th St. N., Pinellas Park, Fla. 33782): "What a scam! The week [before last], the Fed snaps its fingers and creates $2.2 billion, and then uses it to buy $2.2 billion in government debt! What in the hell can you do but laugh at the sheer audacity! Somehow, a government creating more and more money and spending it is not, for the first time in history, going to turn out to be a bad thing? And especially one where the money is just paper and computer blips that they can create on a whim? Of course, I sigh wearily as I note that the banks themselves are in on the scam, and they bought up another $13 billion in government debt [the week before last]. Foreign central banks continue to soak up government debt, and they swallowed another $7.6 billion [that] week, too. The government sells debt to get money to spend on its deficits, and the bank creates the money to buy the debt. Debt and money supply both expand, and it expands to create a bigger and more expensive government! And higher prices. This is economic suicide!"

Indeed, it truly is "economic suicide", but it's even worse than that. It's also monetary homicide. The dollar as we know it is being killed, poisoned by debt from the hand of the federal government with its accomplices in the Federal Reserve and the banking system. So far it's been a slow death, with few people watching, but that's about to change. With the horrific new amounts of debt being injected into the dollar's weary remains, its death is not far off.

Derivatives Out of Control?

When I bring up the topic of derivatives, very few people know what they are, how they work, and most importantly, why should they care. The reason to care is that if left unregulated, as they have been for a very long time, they could conceivably tear the fabric of the global system as we know it. How can that happen? Well, the market is over $270 Trillion and:

This could be a problem.

An excellent article was written in Bloomberg yesterday, that discusses this issue in greater detail.

Credit Derivatives Market Expands to $17.3 Trillion

March 15 (Bloomberg) -- The global market for credit derivatives grew 39 percent to $17.3 trillion in the second half of 2005 on demand for contracts to bet on corporate credit quality or insure against defaults.

Credit-default swaps, which pay compensation in the event of borrowers defaulting on their debt, expanded 105 percent in the full year, leading gains in the overall market for contracts based on underlying assets. Growth slowed from the 123 percent increase in 2004, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association said today in Singapore at its annual meeting.

Regulators are concerned that credit derivatives are growing too quickly for banks to control. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has demanded action to tackle a backlog of contracts left unsigned for months on concern the undocumented transactions threaten the stability of the financial system.

``There's been a certain amount of regulator scrutiny, which may have had some effect'' on growth rates, ISDA Chairman Jonathan Moulds told reporters in Singapore. ``I don't think it's dramatically significant.''

Credit derivatives are the fastest-growing part of the $270 trillion market for derivatives, obligations based on interest rates, events or underlying assets, according to figures from the Bank for International Settlements. The market expanded more than fivefold in two years, according to ISDA.

The trade group represents 700 banks, securities firms and institutional investors that use derivatives.

New York Fed

New York Fed President Timothy Geithner last month said the 10 largest bank holding companies in the U.S. had about $600 billion of potential credit risk from their derivatives holdings. That represents about 175 percent of so-called tier-one capital, the funds banks need to satisfy legal requirements for safety and soundness. Tier-one capital is composed of common stock and retained earnings.

Fourteen of Wall Street's biggest banks committed to cut the number of unsigned trades by 70 percent before July, according to the New York Federal Reserve this week.

Credit-default swaps were designed to protect creditors against non-payment of debts, and some investors now use them to bet on a company's credit quality. Contract buyers pay an annual fee and receive the full amount insured if a borrower defaults. Under the current system, buyers are obliged to deliver the defaulted loans or bonds to the insurer.

When Delphi Corp. collapsed in October, investors held insurance entitling them to more than 10 times the value of the auto-parts maker's bonds. Shortages of notes needed to settle the contracts caused prices for the defaulted bonds to soar.

Interest-Rate Swaps

Contracts to swap between fixed and floating interest payments, the biggest part of the market, increased 6 percent to $213.2 trillion, ISDA said. The growth rate was slower than the 10 percent expansion in the first half, the New York-based group said.

The market for equity derivatives, which let investors speculate on or guard against changes in stock prices, grew 15 percent to $5.6 trillion in the second half, ISDA said. In the full year, the amount expanded 34 percent, compared with 28 percent in 2004.

The figures are based on a survey of as many as 98 firms and include transactions that take place outside exchanges in the so- called over-the-counter market. They reflect the notional amount -- the value of the securities underlying the contracts.

New York Fed President Timothy Geithner last month said the 10 largest bank holding companies in the U.S. had about $600 billion of potential credit risk from their derivatives holdings. That represents about 175 percent of so-called tier-one capital, the funds banks need to satisfy legal requirements for safety and soundness.

This could be a problem.

An excellent article was written in Bloomberg yesterday, that discusses this issue in greater detail.

Credit Derivatives Market Expands to $17.3 Trillion

March 15 (Bloomberg) -- The global market for credit derivatives grew 39 percent to $17.3 trillion in the second half of 2005 on demand for contracts to bet on corporate credit quality or insure against defaults.

Credit-default swaps, which pay compensation in the event of borrowers defaulting on their debt, expanded 105 percent in the full year, leading gains in the overall market for contracts based on underlying assets. Growth slowed from the 123 percent increase in 2004, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association said today in Singapore at its annual meeting.

Regulators are concerned that credit derivatives are growing too quickly for banks to control. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has demanded action to tackle a backlog of contracts left unsigned for months on concern the undocumented transactions threaten the stability of the financial system.

``There's been a certain amount of regulator scrutiny, which may have had some effect'' on growth rates, ISDA Chairman Jonathan Moulds told reporters in Singapore. ``I don't think it's dramatically significant.''

Credit derivatives are the fastest-growing part of the $270 trillion market for derivatives, obligations based on interest rates, events or underlying assets, according to figures from the Bank for International Settlements. The market expanded more than fivefold in two years, according to ISDA.

The trade group represents 700 banks, securities firms and institutional investors that use derivatives.

New York Fed

New York Fed President Timothy Geithner last month said the 10 largest bank holding companies in the U.S. had about $600 billion of potential credit risk from their derivatives holdings. That represents about 175 percent of so-called tier-one capital, the funds banks need to satisfy legal requirements for safety and soundness. Tier-one capital is composed of common stock and retained earnings.

Fourteen of Wall Street's biggest banks committed to cut the number of unsigned trades by 70 percent before July, according to the New York Federal Reserve this week.

Credit-default swaps were designed to protect creditors against non-payment of debts, and some investors now use them to bet on a company's credit quality. Contract buyers pay an annual fee and receive the full amount insured if a borrower defaults. Under the current system, buyers are obliged to deliver the defaulted loans or bonds to the insurer.

When Delphi Corp. collapsed in October, investors held insurance entitling them to more than 10 times the value of the auto-parts maker's bonds. Shortages of notes needed to settle the contracts caused prices for the defaulted bonds to soar.

Interest-Rate Swaps

Contracts to swap between fixed and floating interest payments, the biggest part of the market, increased 6 percent to $213.2 trillion, ISDA said. The growth rate was slower than the 10 percent expansion in the first half, the New York-based group said.

The market for equity derivatives, which let investors speculate on or guard against changes in stock prices, grew 15 percent to $5.6 trillion in the second half, ISDA said. In the full year, the amount expanded 34 percent, compared with 28 percent in 2004.

The figures are based on a survey of as many as 98 firms and include transactions that take place outside exchanges in the so- called over-the-counter market. They reflect the notional amount -- the value of the securities underlying the contracts.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

U.S. vs. China

This is an excellent study in contrasts between the world's only superpower and the world's "emerging" superpower. The relationship between these two countries has become increasingly important and the future of the global economy will be determined by how each country's citizens adapt to the glaring imbalances that have been created over the last 5 years.

The U.S. and China's savings problem

The Chinese have taken thrift to excess, while profligate Americans have spent their way into debt.

By Stephen Roach

March 8, 2006: 6:08 PM EST

(FORTUNE Magazine) - The two major players in the global economy, the U.S. and China, are operating at opposite ends of the saving spectrum. Thrifty Chinese have taken saving to excess, while profligate Americans have spent their way into debt.

Neither of these trends is sustainable -- they lead to destabilizing economic and political developments for both nations -- and a better balance must be struck. China needs to convert excess saving into consumption, while the U.S. needs to end its buying binge and rediscover the art of saving.

The numbers leave little doubt as to the extraordinary contrast between the two economies. Last year China saved about half of its gross domestic product, or some $1.1 trillion. At the same time, the U.S. saved only 13% of its national income, or $1.6 trillion. That's right, the U.S., whose economy is six times the size of China's, can't manage to save twice as much money.

And that's just looking at national averages that include saving by consumers, businesses, and governments. The contrast is even starker at the household level -- a personal saving rate in China of about 30% of household income, compared with a U.S. rate that dipped into negative territory last year (–0.4% of after-tax household income).

Depression-era habits

These are extreme readings by any standard. The U.S. hasn't pushed its personal saving rate this far into negative territory since 1933, in the depths of the Depression. And the Chinese rate is higher than it has been at any point in the past 28 years, since its modern reforms began.

Similar extremes show up in the consumption shares of the two economies -- the mirror image of trends in personal saving rates. U.S. consumption has held at a record 71% of GDP since early 2002, while Chinese consumption appears to have slipped to a record low of about 50% of GDP in 2005.

In China's case, relatively weak consumption means its growth dynamic is skewed heavily toward exports and fixed investment. These two sectors account for more than 75% of Chinese GDP and are growing by more than 25% a year.

If China stays with this growth mix, any further increase on the export side would be a recipe for trade frictions and protectionist responses. That's certainly the direction Washington is heading in these days. Moreover, a continued burst of Chinese investment could lead to excess capacity and deflation at home.

Using homes as ATMs

The U.S. saving shortfall is equally stressful. American consumers have mistaken bubble-like appreciation of their homes for saving. Facing anemic growth in labor incomes -- real compensation paid out by the private sector has lagged behind the norm of past business cycles by more than $360 billion -- they have turned to debt-financed equity extraction from their homes in order to keep consuming. And the binge has reached record highs in terms of both the amount consumers owe as a share of their incomes and the interest expenses they incur to service those obligations.

America's lack of saving has also put unprecedented demands on the rest of the world, since the U.S. must import surplus saving from abroad in order to grow. America's current account deficit hit a record of nearly 6.5% of GDP in 2005 and could well be headed north of 7% this year. That translates into a lifeline of foreign capital totaling about $3 billion per business day.

There is a more insidious connection between the saving postures of China and the U.S.: Chinese savers are, in effect, subsidizing the spending binge of American consumers. In order to fuel its export-led economic growth, China has decided to keep its currency relatively cheap and tightly pegged to the dollar. To do so, it must constantly recycle a large portion of its saving into dollar-denominated financial assets -- an investment strategy that helps keep U.S. interest rates low and an interest-rate-sensitive American housing market in a perpetual state of froth.

That's dangerous for the U.S., but it's also an increasingly risky proposition for China because it bloats that country's money supply. This excess liquidity then spills over into the Chinese financial system, leading to asset bubbles, such as those in its coastal property markets. China is also exposed to the potential fiscal costs of a sharp markdown of its portfolio of dollar-based assets in the event of a depreciation of the U.S. currency.

It is in neither country's best interest to stay the present course. Instead, there must be a role reversal: China's savers must be turned into consumers, and the excesses of U.S. consumption must be converted into saving. This won't be an easy task for either nation, but it sure beats the increasingly treacherous alternatives.

In the U.S., it will take nothing short of a major campaign to boost national saving. That will require a reduction of public-sector dissaving (i.e., outsized federal budget deficits) and the enactment of some form of consumption tax.

A pro-saving agenda

A national sales tax would be the simplest and most efficient prescription, provided there are exemptions for low- and lower-middle-income families. It would reduce incentives for consumption, freeing up income to be saved, and also help reduce the federal deficit.

Sadly, there is little reason to be optimistic that Washington is about to embrace a pro-saving policy agenda. The budget deficit is going the other way, and the lack of political support for tax reform effectively quashes any immediate hopes for private-saving incentives.

In China, it will also take major policy initiatives to spark consumption-led growth. Actions are needed on two fronts -- the establishment of a social-welfare safety net to deal with job and income insecurity arising from reforms of state-owned enterprises; and the creation of new jobs, especially in the undeveloped services sector, to expand the purchasing power of China's enormous population.

The good news is that the Chinese leadership is focused on shifting its growth mix toward private consumption. Pilot projects already have been established setting up a social security system. And under the terms of China's WTO accession, the opening of domestic services to foreign investors in areas like retail and insurance is likely to accelerate over the next three to five years.

China's determination stands in sharp contrast to Washington's inattentiveness to saving initiatives. That could spell trouble. As Chinese saving is converted into consumption, it will have less surplus capital that can be used to fund America's saving shortfall. That means China will be reducing its support for the American consumer. And that would raise the odds of a hard landing for the dollar and the U.S. economy, with dire consequences for a still U.S.-centric global economy.

The U.S. and China need to get their saving agendas in order before it is too late for them -- and for the rest of the world.

Stephen S. Roach is chief economist at Morgan Stanley.

The U.S. and China's savings problem

The Chinese have taken thrift to excess, while profligate Americans have spent their way into debt.

By Stephen Roach

March 8, 2006: 6:08 PM EST

(FORTUNE Magazine) - The two major players in the global economy, the U.S. and China, are operating at opposite ends of the saving spectrum. Thrifty Chinese have taken saving to excess, while profligate Americans have spent their way into debt.

Neither of these trends is sustainable -- they lead to destabilizing economic and political developments for both nations -- and a better balance must be struck. China needs to convert excess saving into consumption, while the U.S. needs to end its buying binge and rediscover the art of saving.

The numbers leave little doubt as to the extraordinary contrast between the two economies. Last year China saved about half of its gross domestic product, or some $1.1 trillion. At the same time, the U.S. saved only 13% of its national income, or $1.6 trillion. That's right, the U.S., whose economy is six times the size of China's, can't manage to save twice as much money.

And that's just looking at national averages that include saving by consumers, businesses, and governments. The contrast is even starker at the household level -- a personal saving rate in China of about 30% of household income, compared with a U.S. rate that dipped into negative territory last year (–0.4% of after-tax household income).

Depression-era habits

These are extreme readings by any standard. The U.S. hasn't pushed its personal saving rate this far into negative territory since 1933, in the depths of the Depression. And the Chinese rate is higher than it has been at any point in the past 28 years, since its modern reforms began.

Similar extremes show up in the consumption shares of the two economies -- the mirror image of trends in personal saving rates. U.S. consumption has held at a record 71% of GDP since early 2002, while Chinese consumption appears to have slipped to a record low of about 50% of GDP in 2005.

In China's case, relatively weak consumption means its growth dynamic is skewed heavily toward exports and fixed investment. These two sectors account for more than 75% of Chinese GDP and are growing by more than 25% a year.

If China stays with this growth mix, any further increase on the export side would be a recipe for trade frictions and protectionist responses. That's certainly the direction Washington is heading in these days. Moreover, a continued burst of Chinese investment could lead to excess capacity and deflation at home.

Using homes as ATMs

The U.S. saving shortfall is equally stressful. American consumers have mistaken bubble-like appreciation of their homes for saving. Facing anemic growth in labor incomes -- real compensation paid out by the private sector has lagged behind the norm of past business cycles by more than $360 billion -- they have turned to debt-financed equity extraction from their homes in order to keep consuming. And the binge has reached record highs in terms of both the amount consumers owe as a share of their incomes and the interest expenses they incur to service those obligations.

America's lack of saving has also put unprecedented demands on the rest of the world, since the U.S. must import surplus saving from abroad in order to grow. America's current account deficit hit a record of nearly 6.5% of GDP in 2005 and could well be headed north of 7% this year. That translates into a lifeline of foreign capital totaling about $3 billion per business day.

There is a more insidious connection between the saving postures of China and the U.S.: Chinese savers are, in effect, subsidizing the spending binge of American consumers. In order to fuel its export-led economic growth, China has decided to keep its currency relatively cheap and tightly pegged to the dollar. To do so, it must constantly recycle a large portion of its saving into dollar-denominated financial assets -- an investment strategy that helps keep U.S. interest rates low and an interest-rate-sensitive American housing market in a perpetual state of froth.

That's dangerous for the U.S., but it's also an increasingly risky proposition for China because it bloats that country's money supply. This excess liquidity then spills over into the Chinese financial system, leading to asset bubbles, such as those in its coastal property markets. China is also exposed to the potential fiscal costs of a sharp markdown of its portfolio of dollar-based assets in the event of a depreciation of the U.S. currency.

It is in neither country's best interest to stay the present course. Instead, there must be a role reversal: China's savers must be turned into consumers, and the excesses of U.S. consumption must be converted into saving. This won't be an easy task for either nation, but it sure beats the increasingly treacherous alternatives.

In the U.S., it will take nothing short of a major campaign to boost national saving. That will require a reduction of public-sector dissaving (i.e., outsized federal budget deficits) and the enactment of some form of consumption tax.

A pro-saving agenda

A national sales tax would be the simplest and most efficient prescription, provided there are exemptions for low- and lower-middle-income families. It would reduce incentives for consumption, freeing up income to be saved, and also help reduce the federal deficit.

Sadly, there is little reason to be optimistic that Washington is about to embrace a pro-saving policy agenda. The budget deficit is going the other way, and the lack of political support for tax reform effectively quashes any immediate hopes for private-saving incentives.

In China, it will also take major policy initiatives to spark consumption-led growth. Actions are needed on two fronts -- the establishment of a social-welfare safety net to deal with job and income insecurity arising from reforms of state-owned enterprises; and the creation of new jobs, especially in the undeveloped services sector, to expand the purchasing power of China's enormous population.

The good news is that the Chinese leadership is focused on shifting its growth mix toward private consumption. Pilot projects already have been established setting up a social security system. And under the terms of China's WTO accession, the opening of domestic services to foreign investors in areas like retail and insurance is likely to accelerate over the next three to five years.

China's determination stands in sharp contrast to Washington's inattentiveness to saving initiatives. That could spell trouble. As Chinese saving is converted into consumption, it will have less surplus capital that can be used to fund America's saving shortfall. That means China will be reducing its support for the American consumer. And that would raise the odds of a hard landing for the dollar and the U.S. economy, with dire consequences for a still U.S.-centric global economy.

The U.S. and China need to get their saving agendas in order before it is too late for them -- and for the rest of the world.

Stephen S. Roach is chief economist at Morgan Stanley.

Monday, March 06, 2006

Welcome to Capitalism China!

China is now discovering what we, in the most prosperous nations of the world, have known for years. A bust usually follows a boom. As housing prices go up to ridiculously unsustainable levels, what follows, is usually not a pretty sight. Those silly Chinese people who are learning this for the first time. If only they had the wisdom of North Americans who know better, who have had the experience of many past bubbles to draw from, and would never caught up in a housing bubble...okay I'm done with my sarcasm. All I can say is, China's real estate bubble burst first and America will follow soon!

March 4, 2006, 7:25PM

Shanghai's housing bubble bursts, causing some panic

Bust follows a doubling of prices in past three years; recent buyers sue to get money back

By DON LEE

Los Angeles Times

Shanghai's red-hot housing boom has hit the skids, as an oversupply of homes fueled by speculators has chilled the market.

SHANGHAI, CHINA - American homeowners wondering what follows a housing bubble can look to China's largest city.

Once one of the hottest markets in the world, sales of homes have virtually halted in some areas of Shanghai, prompting developers to slash prices and real estate brokerages to shutter thousands of offices.

For the first time, homeowners here are learning what it means to have an upside-down mortgage — when the value of a home falls below the amount of debt on the property. Recent home buyers are suing to get their money back. Banks are fretting about a wave of defaults on loans.

"The entire industry is scaling back," said Mu Wijie, a regional manager at Century 21 China, who estimated that 3,000 brokerage offices had closed since spring. Real estate agents, whose phones wouldn't stop ringing a year ago, say their incomes have plunged by two-thirds.

Shanghai's housing slump is only going to worsen and imperil a significant part of the Chinese economy, says Andy Xie, Morgan Stanley's chief Asia economist in Hong Kong.

Although the city's 20 million residents represent less than 2 percent of China's population of 1.3 billion, Xie says, Shanghai accounts for an astounding 20 percent of the country's property value. About 1 million homes in Shanghai alone — about half the number of housing starts for the entire United States in 2004 — are under construction.

"They'll remain empty for years," Xie said, adding that a jolting comedown also was in store for other Chinese cities with building booms — including Beijing, Chongqing and Chengdu — though other analysts say the problem is largely confined to Shanghai.

Shanghai's housing bust comes after a doubling of prices in the previous three years, a run-up fueled by massive speculation.

With China's economy booming and Shanghai at the center of worldwide attention, investors from Hong Kong, Taiwan and elsewhere were buying as fast as buildings were going up. At least 30 percent to 40 percent of homes sold were bought by speculators, says Zhang Zhijie, a real estate analyst at Soufun.com Academy, a research group in Shanghai.

"Ordinary people had no option but to follow the trend," Zhang said. "Worrying that prices would be even more unaffordable tomorrow, many of them borrowed from relatives and banks to buy as soon as possible."

The Shanghai government only pushed the market higher, he added. "Many of the officials said Shanghai's property market was healthy and wouldn't drop before the World Expo" in 2010.

For Wang Suxian, 35, the tale of two lines illustrates how the bubble has burst.

When home prices were at the tail end of the boom in March 2005, Wang hired two migrant workers to stand in line for a chance to buy units in what the developer said was modeled after an apartment community on New York's Park Avenue.

The workers waited 72 hours but Wang was thrilled to come away with two apartments, one for $110,000, about the average price for a new home in Shanghai, and another for $170,000. They were among Wang's four investment properties.

And for a short period, Wang believed she was raking in hundreds of dollars a day for doing nothing, as property prices in the city kept soaring.

But today, prices at the apartment complex have fallen by one-third, and the lines of frenzied buyers are gone. Wang is among dozens who are fighting the developer to take the apartments back.

On a recent morning, she stood in a line herself with about 40 other buyers outside the builder's headquarters, demanding that it negotiate a deal to return their money. The company, Da Hua Group, invited Wang and other homeowners inside, served them hot tea, then told them to forget it.

"I think it'll take at least three years before the property market becomes healthy again," Zhu Delin, a professor of finance at Shanghai University and former head of the Shanghai Banking Association, predicted.

The typical home being built is in a high-rise complex, with two bedrooms and about 850 square feet of living space.

March 4, 2006, 7:25PM

Shanghai's housing bubble bursts, causing some panic

Bust follows a doubling of prices in past three years; recent buyers sue to get money back

By DON LEE

Los Angeles Times

Shanghai's red-hot housing boom has hit the skids, as an oversupply of homes fueled by speculators has chilled the market.

SHANGHAI, CHINA - American homeowners wondering what follows a housing bubble can look to China's largest city.

Once one of the hottest markets in the world, sales of homes have virtually halted in some areas of Shanghai, prompting developers to slash prices and real estate brokerages to shutter thousands of offices.

For the first time, homeowners here are learning what it means to have an upside-down mortgage — when the value of a home falls below the amount of debt on the property. Recent home buyers are suing to get their money back. Banks are fretting about a wave of defaults on loans.

"The entire industry is scaling back," said Mu Wijie, a regional manager at Century 21 China, who estimated that 3,000 brokerage offices had closed since spring. Real estate agents, whose phones wouldn't stop ringing a year ago, say their incomes have plunged by two-thirds.

Shanghai's housing slump is only going to worsen and imperil a significant part of the Chinese economy, says Andy Xie, Morgan Stanley's chief Asia economist in Hong Kong.

Although the city's 20 million residents represent less than 2 percent of China's population of 1.3 billion, Xie says, Shanghai accounts for an astounding 20 percent of the country's property value. About 1 million homes in Shanghai alone — about half the number of housing starts for the entire United States in 2004 — are under construction.

"They'll remain empty for years," Xie said, adding that a jolting comedown also was in store for other Chinese cities with building booms — including Beijing, Chongqing and Chengdu — though other analysts say the problem is largely confined to Shanghai.

Shanghai's housing bust comes after a doubling of prices in the previous three years, a run-up fueled by massive speculation.

With China's economy booming and Shanghai at the center of worldwide attention, investors from Hong Kong, Taiwan and elsewhere were buying as fast as buildings were going up. At least 30 percent to 40 percent of homes sold were bought by speculators, says Zhang Zhijie, a real estate analyst at Soufun.com Academy, a research group in Shanghai.

"Ordinary people had no option but to follow the trend," Zhang said. "Worrying that prices would be even more unaffordable tomorrow, many of them borrowed from relatives and banks to buy as soon as possible."

The Shanghai government only pushed the market higher, he added. "Many of the officials said Shanghai's property market was healthy and wouldn't drop before the World Expo" in 2010.

For Wang Suxian, 35, the tale of two lines illustrates how the bubble has burst.

When home prices were at the tail end of the boom in March 2005, Wang hired two migrant workers to stand in line for a chance to buy units in what the developer said was modeled after an apartment community on New York's Park Avenue.

The workers waited 72 hours but Wang was thrilled to come away with two apartments, one for $110,000, about the average price for a new home in Shanghai, and another for $170,000. They were among Wang's four investment properties.

And for a short period, Wang believed she was raking in hundreds of dollars a day for doing nothing, as property prices in the city kept soaring.

But today, prices at the apartment complex have fallen by one-third, and the lines of frenzied buyers are gone. Wang is among dozens who are fighting the developer to take the apartments back.

On a recent morning, she stood in a line herself with about 40 other buyers outside the builder's headquarters, demanding that it negotiate a deal to return their money. The company, Da Hua Group, invited Wang and other homeowners inside, served them hot tea, then told them to forget it.

"I think it'll take at least three years before the property market becomes healthy again," Zhu Delin, a professor of finance at Shanghai University and former head of the Shanghai Banking Association, predicted.

The typical home being built is in a high-rise complex, with two bedrooms and about 850 square feet of living space.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)